A geezers guide to: TAG Heuer The brand with a Need for Speed

Ah, TAG Heuer. If there’s one watch brand that likes to think it's been revving up the horological world like a Formula 1 car on steroids, it’s this one. From the early beginnings of a 20-year watchmaker living on his family farm to dominating the ‘bang average’ sector of the industry, this is the tale of one of the most iconic brands in watchmaking.

In todays world, the brand has become the unofficial timekeepers of athletic adrenaline junkies and middle aged blokes alternating from the fruit machines to the snooker table in your local pub. But TAG Heuer’s story isn't just about speed and machismo — it’s also about diversification. Because why just make watches when you can dabble in everything from luxury smartphones to belt driven tourbillons and 5/10,000/sec chronographs?

So, buckle up. Let’s dive into the turbocharged history of TAG Heuer, a brand that isn’t afraid to mix classic Swiss watchmaking with a healthy dose of we’re-too-cool-for-this-bullshit business ventures. You might just leave wondering, “How does a classic brand that started with chronograph developments end up being named after a tax haven based, Middle easten founded holding company trying to be the serious face of Formula 1 while selling a £40,000 Mario Kart tourbillon to people who don't even drive?”

The Early Years of Heuer: Pioneering Precision and Innovation (1860-1900)

In 1860, Edouard Heuer, a young Swiss watchmaker with a dream, set up his first workshop in St-Imier, Switzerland. This was in an era where watches were serious business—none of this “lifestyle accessory” nonsense. Heuer had one mission: making precision timepieces to help people do important things, like timing horse races or calculating the distance from enemy artillery.

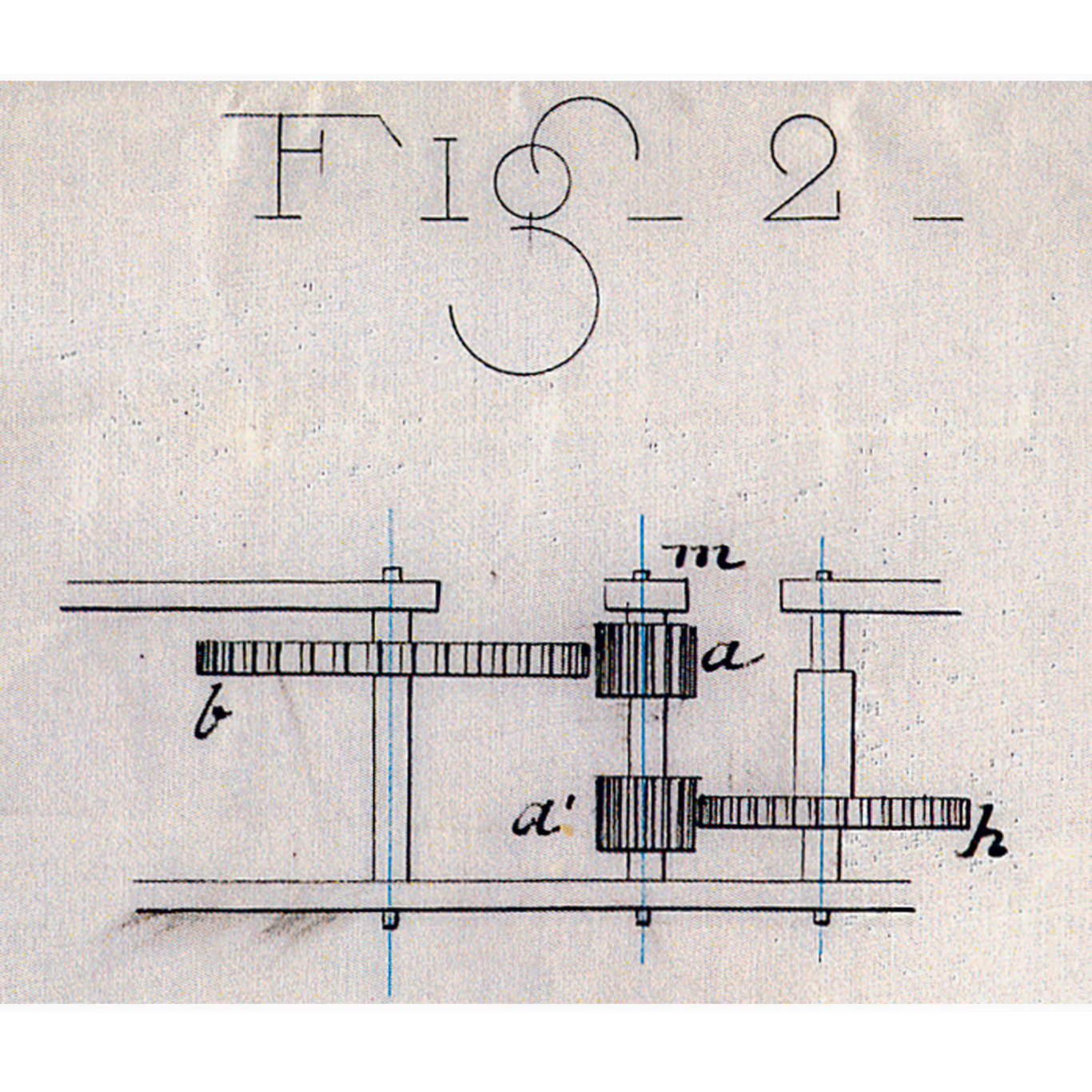

By 1887, Heuer had already made his mark with the oscillating pinion, a breakthrough in chronograph design that made timing things smoother and cheaper. An arbor with two pinions is erected upon activation of the chronograph and transmission is connected from the fourth wheel of the going train to the chronograph seconds wheel. When the arbor is tilted away, the teeth come out of engagement and the chronograph stops running. The advantages of this clutch are that there is less dead weight (non-moving wheels in the chronoworks that need lots of energy to overcome its moment of inertia), and the smaller tooth profiles of the meshing pinion and wheel allow a quicker, smoother launch of the chronograph. The advantage both of these have is that on activation, the amplitude will have a smaller drop as less energy is needed to wake the chrono train.

To this day, a lot of modern chronographs still use a version of this mechanism—one of the few genuine contributions to watchmaking history that TAG Heuer hasn’t yet managed to over advertise in everyone's face (cough cough, we're looking at you omega).

Heuer 1910–1940: The Glory Days of Timing Things Properly

Before Heuer became the motorsport-obsessed, celebrity-endorsed beast it is today, it was actually making watches for people who needed them, not just for those looking to flex on Instagram. Between 1910 and 1940, Heuer was the name in precision timing, strapping itself to the wrists, dashboards, and cockpits of racers, aviators, and Olympic athletes—back when sports timing involved actual mechanical genius rather than a bloke with a laptop.

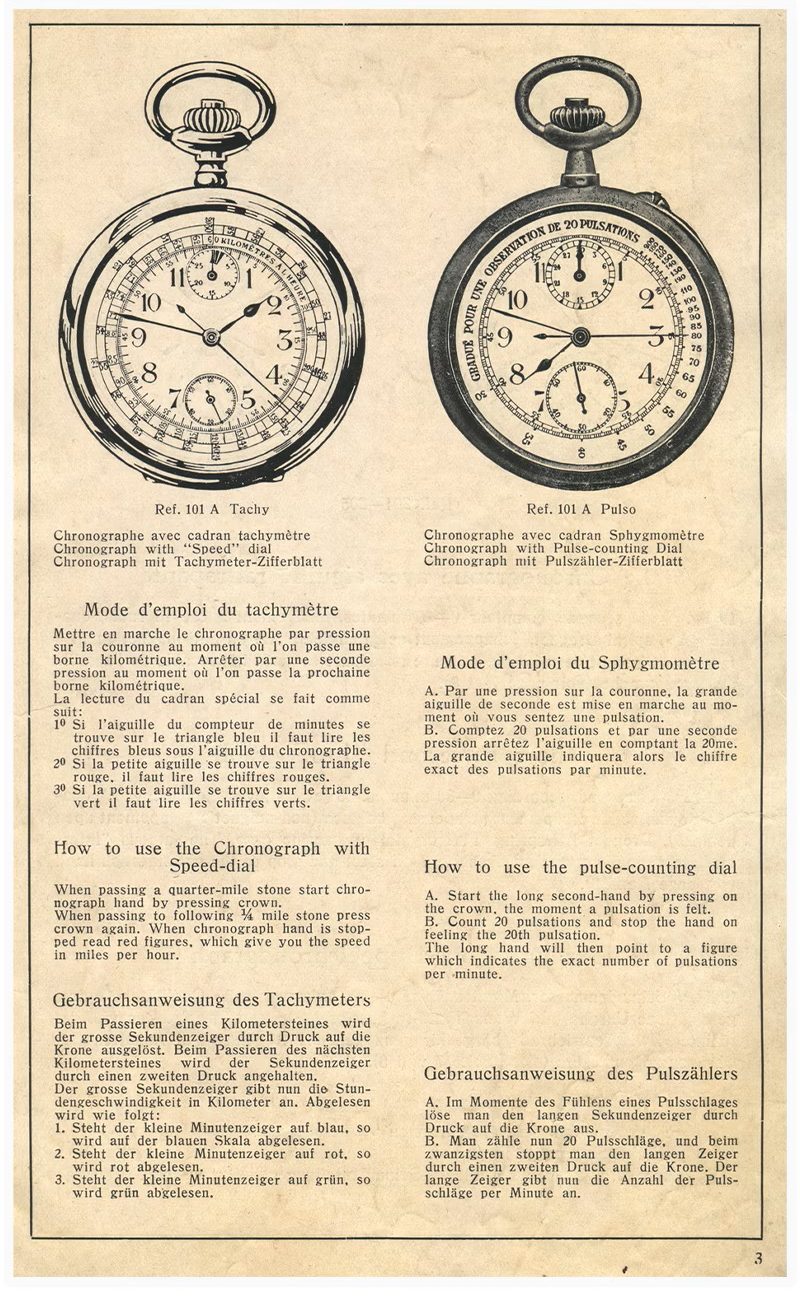

1908: The Heuer Sphygmometer - is dial printing an innovation?

Charles-Auguste Heuer decided to dabble in the medical field. In 1908, after what we can only assume was a particularly long and tedious doctor's visit, he came up with the Sphygmometer pocket chronograph. Unlike your standard chronograph, this one had a colourful scale designed to let doctors, or anyone pretending to be one, measure a patient’s heart rate in just 20 seconds.

This was revolutionary at the time—no more manually counting beats for a full minute like some sort of human abacus. Instead, you just started the chronograph, counted for 20 seconds, and the scale did the math for you. It was like an early attempt at medical automation, except instead of computers, you had Swiss mechanics and a very patient doctor.

Did it change the world? Not quite. But it was one of the first examples of Heuer applying chronograph tech beyond the racetrack, proving that good timing wasn’t just for speed demons—it was for doctors, too.

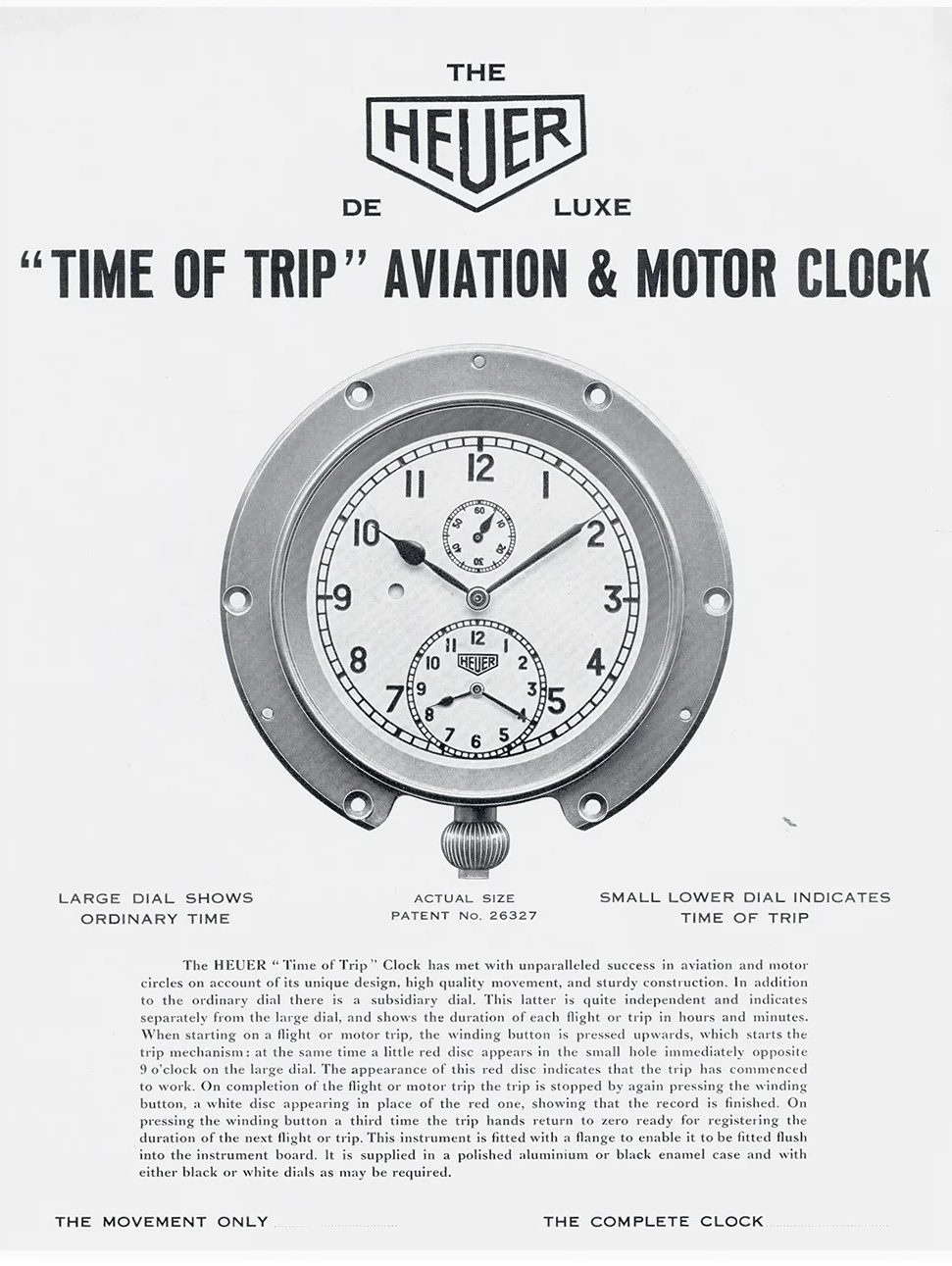

1911: The Dashboard Domination Begins

In 1911, Heuer introduced the Time of Trip, a dashboard-mounted chronograph for cars and planes. This was back when pilots and race car drivers had a roughly 50/50 chance of surviving their adventures, so knowing the time to the exact second was somewhat important. The clock worked by showing the time on the main dial and then the duration of the journey or ‘time of trip’ on a subdial. The clever part is that the time of trip is reset to zero using the pusher, making restart instant. If you were tearing through the skies in a rickety biplane, Heuer was your best bet for timing how long you had before an engine failure ruined your day.

1916: The Mikrograph—When 1/5th of a Second Wasn’t Enough

If you thought Heuer was just going to sit back and pump out regular chronographs, think again. In 1916, they released the Mikrograph, the world's first stopwatch accurate to 1/100th of a second. The cooler brother (with a terrible name), Semikrograph offered 1/50th of a second accuracy with a split second complication. These watches were seriously groundbreaking. So much so that the Olympics adopted it in 1920 —because, of course, the difference between gold and silver medals had to be measured in fractions of a blink.

1920s & 1930s: Timing Everything That Moves

Due to these innovations, Heuer was the undisputed king of sports timing, supplying gear for the Olympics, F1, Indy 500, athletics, sailing, alpine events and anything else that involved speed and competition. This was when the brand's partnership was actually technical and used in the cockpit or at race control as opposed to merely printed on the tight lycra of an athlete's well nourished torso.

1933: The Birth of the Autavia (Sort Of)

In 1933, Heuer introduced the Autavia, but not as the wristwatch we know today—this was a dashboard timer for automobiles and aviation (hence the name Autavia—a mash-up of “AUTOmobile” and “AVIAtion”). It was the kind of thing that racing teams and pilots actually relied on, long before it became a reissued hype piece for collectors.

1935–1940: Military & Pilot Chronographs Take Over

By the late 1930s, Heuer was supplying Flieger (pilot) chronographs to various air forces, because nothing says “precision under pressure” like a well-made mechanical chronograph in the middle of a dogfight. These watches were no-nonsense, legible, and built to survive ridiculous conditions—basically the opposite of half the fragile luxury pieces TAG Heuer pumps out today.

1957: the ringmaster

With Heuer dabbling in as many applications as possible with different chronograph scales, a clever exec decided to pitch a questionably named watch, ‘the ring master’… The pocket stopwatch had a detachable glass and interchangeable scales around the outside of the dial, allowing the operator to use the watch to time anything. From timing rounds and breaks of a boxing match, to showing decimalised minutes for rallying. It makes me wonder if they ever thought of selling blank rings allowing the owner to invent their own scales for the most important of activities like checking the barman has poured ‘an acceptable Guinness’, to simultaneously monitor the cooking of steaks, burgers and sausages on the BBQ.

The 1958 Seafarer: When Heuer Got Fancy (Sort Of)

In 1958, Heuer made a rare venture into complications beyond a stopwatch with the Abercrombie & Fitch Seafarer—a wrist-worn chronograph dubbed the mareographe with a tide indicator and regatta timer for sailors. Yes, Abercrombie & Fitch was a proper outfitter before it became an inofensive shopping mall brand, and back then, this watch was pretty cool. It was one of the first chronographs with a tide function, proving that Heuer could do more than just a simple chronograph.

The Carrera: When Heuer Hit the Gas (1960–1975)

Back to motorsport. By the 1960s, Heuer really was the name in motorsport timing with stopwatches, dashboard clocks, and wristwatches built for people who actually needed to measure time while doing 150mph in an open-top deathtrap. But one thing was missing: a properly designed racing chronograph that wasn’t just a repurposed dress watch with a tachymeter slapped on. Enter the Carrera, the watch that defined Heuer’s golden era and still makes the modern brand worth talking about.

1963: The Birth of the Carrera

In the early '60s, Jack Heuer (the man who made Heuer cool before it was TAGged up) wanted a watch that reflected the spirit of racing—clean, legible, and purpose-built. He found inspiration in the Carrera Panamericana, a Mexican road race so dangerous and unhinged that it got shut down after five years. Heuer figured that if a race was fast, deadly, and glamorous, it deserved a watch.

Thus, the Carrera 2447 was born in 1963—a 39mm, no-nonsense chronograph with a perfectly balanced dial and an emphasis on legibility. It had a minimalist design—no clutter, no extra nonsense—because when you’re timing lap after lap, you don’t need an extra 12 complications to confuse you.

The Mid-'60s: Heuer Becomes the Racer’s Choice

Throughout the 1960s, the Carrera became the go-to watch for professional and amateur racers. It had a Valjoux manual-wind movement, an incredibly clean dial layout, and a design ethos that made it one of the most timeless chronographs ever made. Unlike some brands (cough Rolex cough), Heuer wasn’t making watches for people to show off, this was a true racing tool.

Jack Heuer personally made sure the Carrera landed on the wrists of actual racing legends, and by the end of the decade, Heuer was synonymous with motorsport. But then, something big happened: the race for the first automatic chronograph.

1969: The Calibre 11 & the Automatic Revolution

By the late '60s, watchmakers were scrambling to create the first automatic chronograph movement. Seiko, Zenith, and a Heuer-led consortium (including Breitling and Buren) were in a three-way race to make history. Heuer’s team came out with the Calibre 11, a left-hand crown automatic chronograph that powered the Carrera, Monaco, and Autavia.

The automatic Carrera (Ref. 1153) was a game-changer—a sleeker case, funky 1970s styling, and that offbeat left-hand crown that screamed, “Look, no winding!” It wasn’t as refined as Zenith’s El Primero, but it got the job done and looked damn good doing it.

1970s: Heuer Goes Full Motorsport

By the early 1970s, Heuer was cemented as the racing chronograph brand. Ferrari’s F1 team was decked out in Heuer stopwatches, dashboard timers, and wristwatches, and drivers like Niki Lauda and Clay Regazzoni were strapping Carreras to their wrists. You weren’t a serious racer in the ‘70s unless you had a Heuer—or at least a good excuse for why you didn’t.

But while motorsport was thriving, the Quartz Crisis was lurking in the shadows. By the mid-‘70s, cheap, accurate quartz watches were starting to destroy the mechanical watch industry, and even a brand as deeply entrenched in motorsport as Heuer wasn’t safe.

1975: The Beginning of the End (For Now)

By the mid-‘70s, the Carrera had evolved into funkier, bigger designs that leaned heavily into 1970s trends—cushion cases, bold colors, and integrated bracelets. But the writing was on the wall: mechanical watches were on life support, and Heuer was about to face its biggest challenge yet.

Desperate Times, Funky Watches

Having one foot on the racetrack and the other in financial quicksand. The Carrera was still a motorsport icon, but started losing its ground to cheap soulless quartz watches. In the coming years, Heuer did what many Swiss brands did—it jumped on the quartz bandwagon. Out came the Heuer Chronosplit in 1975, an early attempt at a digital-analog hybrid that was either ahead of its time or a crime against good taste, depending on how you look at it.

This era gave birth to the quartz-powered Carreras, because if you can’t beat the enemy, you might as well slap their tech into your best-selling model and hope no one notices. By the end of the ‘70s, Heuer had one foot in the past (mechanical racing chronographs) and one foot in a very uncertain future (quartz everything).

Despite Heuer’s efforts to keep the brand relevant, the company was in financial freefall. The mechanical Carrera was now essentially dead. Heuer was bleeding cash, and the only thing keeping the brand afloat was its strong ties to motorsport and its reputation for making accurate timepieces—but reputation alone doesn’t pay the bills.

By 1982, Heuer was officially on the ropes. Enter TAG (Techniques d’Avant Garde)—a company better known for funding turbocharged F1 engines at McLaren, than making watches. In 1985, TAG bought Heuer, and just like that, the brand went from being a family-run Swiss watchmaker to part of a corporate conglomerate.

1985: Welcome to TAG Heuer – The ‘80s Makeover

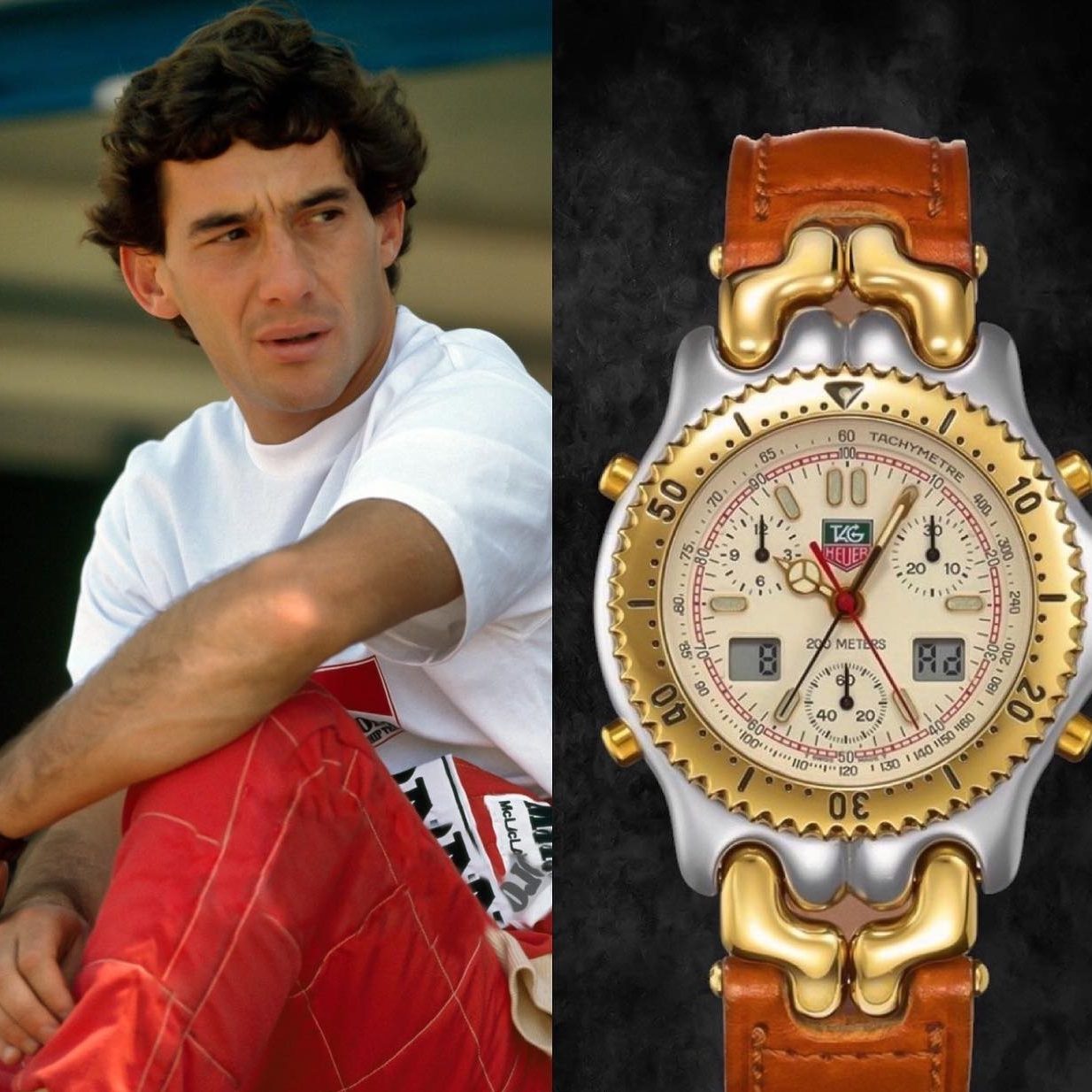

With fresh money from TAG, Heuer became TAG Heuer, and the focus shifted hard toward modern, high-tech sports watches. This wasn’t necessarily a bad thing—the brand started pumping out quartz-powered, ultra-accurate chronographs that actually made sense for a world obsessed with digital precision. Bringing the price points of their watches down and appealing to a wider market obviously worked, but as we look back we start to wonder who and what exactly did TAG do before the acquisition of Heuer?

TAG’s Origins: Oil Money, Aviation, and High-Tech Obsession

TAG wasn’t a watch company. It was founded in 1977 by Akram Ojjeh, a Saudi businessman who loved high-tech investments and had a knack for funding game-changing engineering projects. The company specialized in high-end manufacturing, aeronautics, and motorsport technology, meaning its interests were way beyond just fancy wristwatches.

Before acquiring Heuer, TAG had similar interests as motorsport obsessed Heuer. They were best known for bankrolling McLaren’s F1 engines. They teamed up with Porsche to create the TAG-Porsche Turbo V6 engine, which powered McLaren to back-to-back Formula 1 World Championships in the mid-‘80s with Niki Lauda and Alain Prost at the wheel.

That’s right—TAG wasn’t just slapping its logo on an F1 car like a modern sponsorship deal. It was actually funding the development of race-winning engines, proving that this wasn’t just a rich guy’s vanity project. With core interests aligned, could this partnership be a beautiful marriage?

In 1985, TAG officially acquired Heuer, renaming it TAG Heuer and steering it in a more modern, sporty, and technology-driven direction. The focus wasn’t just on heritage—it was about making watches that fit the high-performance, motorsport-loving crowd.

This is when we got the TAG Heuer Formula 1, a fun, affordable, and very ‘80s quartz watch that looked like it either came with a happy meal and/or belonged on the wrist of a Ferrari Testarossa owner. It wasn’t as iconic as the Carrera, but it kept TAG Heuer alive while the brand figured out its next moves.

TAG’s Other Ventures: Beyond Watches

TAG didn’t just buy Heuer and call it a day—the group had plenty of high-tech ambitions, including:

1. TAG-McLaren Partnership (1980s–1990s)

TAG continued to be deeply involved with McLaren F1 even after its Porsche engine project. The company’s name stayed on McLaren’s F1 team, and it even had a stake in the team’s ownership for a while. This partnership further cemented TAG Heuer as THE motorsport watch brand.

2. TAG Electronics & Aviation Tech

TAG wasn’t just throwing money at race cars. It also had interests in high-end electronics and aerospace engineering. It was involved in developing advanced telemetry systems for motorsport, aviation, and defense applications.

3. TAG Group’s Ownership of McLaren Cars (1980s–1990s)

Yes, TAG really owned a chunk of McLaren’s road car division. This meant it played a role in the creation of the legendary McLaren F1 road car in the ‘90s—arguably the greatest supercar ever made.

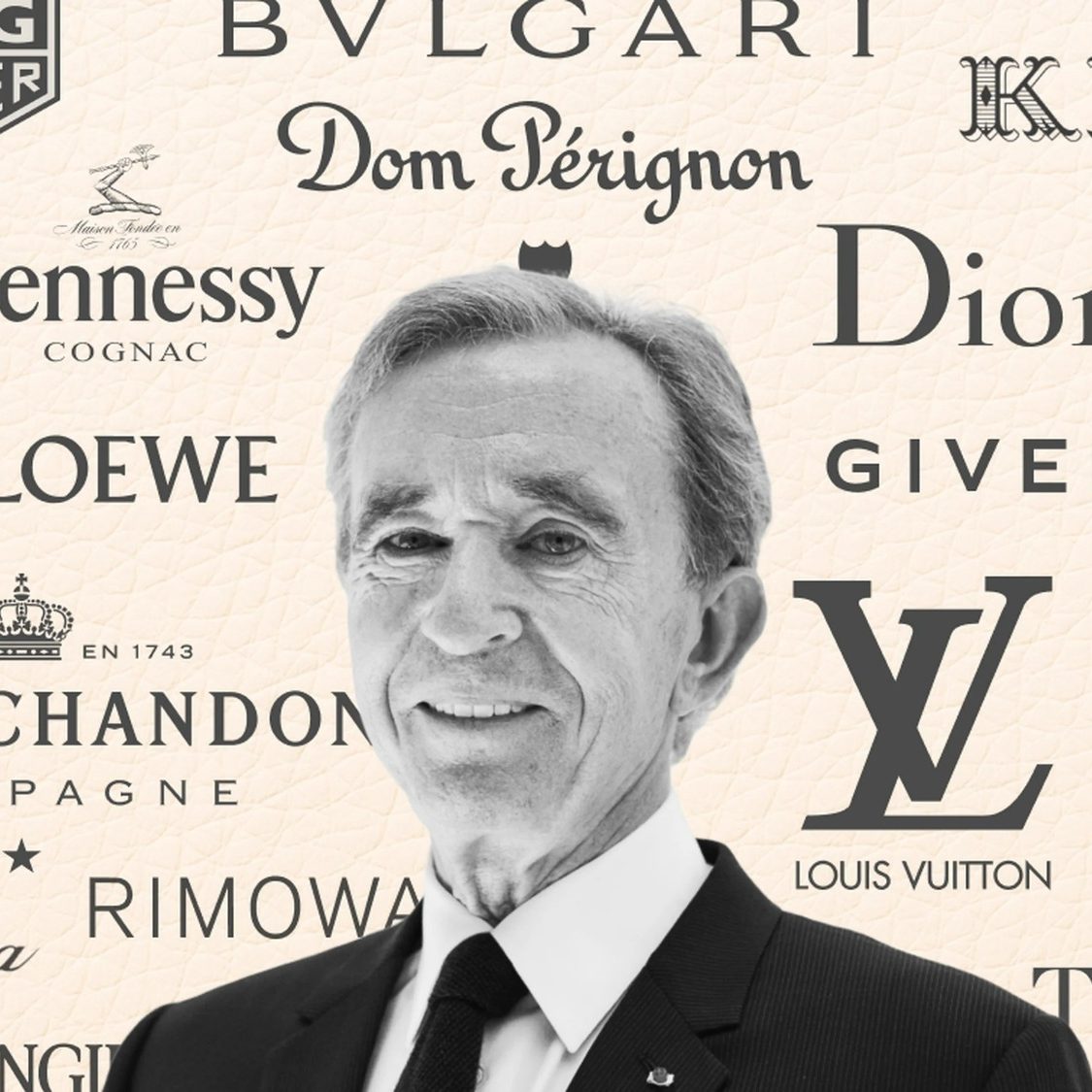

The End of TAG’s Involvement with TAG Heuer

Back to watches. By the late ‘90s, TAG Heuer was back on solid ground, but TAG itself wasn’t as interested in watches anymore. In 1999, TAG Heuer was sold to LVMH (Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy), marking the end of TAG Group’s direct involvement with the brand.

TAG, however, continued its legacy in high-performance engineering, eventually selling off its McLaren shares but remaining a powerful name in motorsport technology and luxury innovation.

1999–Present: TAG Heuer Joins the LVMH Luxury Circus

By 1999, TAG Heuer was doing alright for itself—not dead, not thriving, but surviving. TAG Group had steered the brand through the quartz crisis and turned it into a modern, sporty watch brand with heavy ties to motorsport. But in the world of luxury, "doing alright" isn’t good enough. So along came LVMH (Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy), the French luxury juggernaut that collects high-end brands the way some people collect G-Shocks.

For $739 million, LVMH scooped up TAG Heuer and tossed it into the same portfolio as Zenith, Hublot, and Bulgari—which meant the brand was now under the same corporate umbrella as champagne, handbags, and overpriced designer trainers. What could possibly go wrong?

The 2000s: “Let’s Make TAG Heuer Fancy Again”

LVMH didn’t buy TAG Heuer to let it keep cranking out mid-range quartz sports watches—they wanted to make it properly luxury again. The solution? Bring back mechanical watches and dig into Heuer’s motorsport heritage.

Big moves during this era:

- The Carrera was resurrected in 2004 with a proper mechanical movement, reminding everyone that TAG Heuer used to make serious racing watches before it got distracted by quartz and plastic.

- The Monaco was revived with an in-house movement and more prestige, officially graduating from 1970s cult classic to modern luxury status symbol.

- TAG Heuer started making higher-end mechanical watches, such as the Calibre 360 (a 1/100 second mechanical chronograph). A clever release because this feat was already accomplished by Heuer 100 years ago with the 1916 Mikrograph, but they advertised this as a breakthrough in innovation.

The brand was leaning into serious watchmaking again, and by the mid-2000s, it was back on collectors’ radars. But remember the age old saying?, things have to get worse before they get better.

The TAG Heuer Smartphone: Because Why the Hell Not?

Ah to be back in 2008. The world was going to shit and all I can remeber from this time was playing wii sports in the living room while my parents were arguing about mortgage and fear of redundancies in the kitchen. And at the time of uncertainty, triggered by perpetuated greed in the banking sector, the puppet masters at lvmh were releasing a 5000 pound smart phone.

Enter the TAG Heuer Meridiist—a flip phone (yes, in 2008, when iPhones were already a thing) with Sapphire crystal screens, a stainless steel body, and a battery life that could last a week. Sounds great, right? Well, here’s the catch—it cost over $5,000 and ran the same kind of basic OS you’d find on a burner phone in a crime drama. But hey, it had a tiny secondary OLED screen on top for checking the time, because why would you use your actual watch for that?

The Meridiist was TAG Heuer's first attempt at the luxury tech game, and shockingly, it didn’t die immediately. In 2011, they followed up with the Link Phone, an Android-powered luxury smartphone that cost upwards of $6,000. It was built like a tank, covered in leather, gold, and titanium, and featured a completely unremarkable spec sheet. Think of it as the Hublot of smartphones—flashy, expensive, and a crap.

Then in 2015, TAG Heuer finally wised up and pivoted to smartwatches, launching the TAG Heuer Connected—a high-end Android Wear watch that at least made sense for the brand. Meanwhile, the smartphone experiment quietly died, leaving behind a handful of rich people with gold-plated flip phones and a cautionary tale about luxury brands trying to enter the tech world.

The 2010s: The Hublot-ication continues

By the time Jean-Claude Biver (the man who revived Blancpain and turned Hublot into a cash machine selling cheap watches to footballers for a huge markup) took over in 2014, TAG Heuer was doing well, but it needed a fresh strategy. His plan? Split the brand into two worlds:

- Luxury heritage pieces (Carrera, Monaco, and Autavia reissues for the purists)

- High-tech, aggressively marketed watches aimed at people who think the Hublot Big Bang is an attractive watch.

Enter the Smartwatches and Tourbillons

- In 2015, TAG Heuer launched the aforementioned Connected, its first luxury smartwatch—essentially a very expensive Android Wear watch for people who don’t mind spending 1,500 quid on something that will be outdated in four years.

- Then they dropped the TAG Heuer Carrera Heuer-02T Tourbillon, a Swiss tourbillon for under $20,000—massively undercutting its rivals.

To a lot of enthusiasts' minds it worked—TAG Heuer was making headlines again.

This era saw TAG Heuer embracing both tradition and modern gimmicks, trying to be everything to everyone.

The 2020s: TAG Heuer Settles Into Its Identity Crisis

Today, TAG Heuer is a brand of contradictions. It still makes legitimately great mechanical watches (Carrera Chronograph, Monaco, arguably the Autavia), but it also leans hard into high-tech and hype marketing (NFT watches, Mario Kart collabs, and influencer-heavy campaigns).

The Good:

- The Carrera Glassbox (2023) proved that TAG Heuer still knows how to make a damn good vintage-inspired mechanical chronograph.

- The Monaco remains one of the coolest watches ever, still tied to motorsport and still reminding us Steve McQueen looks cooler than us.

The Questionable:

- The Connected Smartwatches are still a thing, because someone out there is buying them.

- Limited editions galore—because why release one good Carrera when you can make 15 fairly decent ones?

Final Verdict: Where is TAG Heuer Now?

TAG Heuer in 2025 is basically a tale of two brands:

- The smart, civilised west end, it’s a serious watchmaker bringing back heritage-inspired, well-crafted mechanical watches that collectors genuinely respect.

- On the other side, it’s a marketing-driven machine, making smartwatches, Ronda-powered F1’s priced far too high, and questionable collaborations chasing trends.

Heuer is a strange brand. It has a deep rich history with quite a few genuine innovations and iconic watches. But it also has a tackier, funkier side we wish to forget. Why is it still named after the Saudi holding company that saved but tarnished the brand's reputation? Why does LVMH treat it like some experiment in hype marketing? But the main question I have is why do we care? It may sometimes be cringey and painful to endure but it's upwards trajectory is clear and hey, at least this wild ride we have been taken on isn't a boring one!

While you're here, why not check out this list of our favourite Heuers on the market

Here are 6 Heuers we think are far more interesting than anything the brand has for sale right now…

For the ultimate Heuer collection, an Audi Sport chronograph optimizes the brand's chronograph and motorsport infused identity. In the era of Quatro this collaboration created an unapologetically 80s design. Being new old stock this is the go to example to get.

The clean layout carerras are what Heuer did best. 36mm with a manual wound movement is a match made in heaven. The red coloring of the tachymeter scale gives a nice contrast which is a great bonus!

Funky case design, simple colours and central chrono minutes at 1500 quid, you cannot go wrong.

The Heuer trackstar was largely circulated to sports institutions and not direct to consumer. And we can't tell which institution these were delivered to because it times literally any sport on the dial, including Australian football… whatever that is.

Okay, you can debate whether this is an actual watch or not, as it doesn't actually tell the time. But does this not scream 80’s Heuer!? The chances are high you won't be timing actual yacht racing, instead timing day to day intervals such as your coworker yapping on about their favourite box-set for the third time this fortnight. Don't expect high-quality craftsmanship here. Inside you will find an unadjusted 7 jewel movement, but chances are high that you will have the rarest and probably most interesting watch of any room you walk in, and in today's wrist watch circle jerk society, you might be able justify the £1100 price tag

Alright, again, it doesn't really count because it's not a watch but we just had to include it. Years have passed and Maserati levels of depreciation mean that with the new trend of ‘dumbphones’ this could be a pretty cool piece to pick up at a fraction of its retail price. Only god knows if any apps will work on this thing, but this could be the quirkiest way of curing your Instagram (@geezerswithtweezers) reels addiction.

©Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.